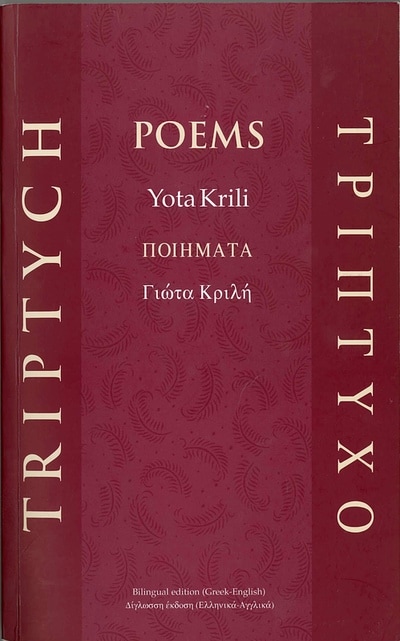

Triptych - Τρίπτυχο

Publication Series: Writing the Greek Diaspora

Triptych includes three collections of poems by the bilingual poet Yota Krili.

Patchwork is a quilt of poems reflecting the rich diversity of life.

Memories vividly evokes people and events of a past in Greece.

Laya is a poetic exploration of the migrant experience.

Patchwork is a quilt of poems reflecting the rich diversity of life.

Memories vividly evokes people and events of a past in Greece.

Laya is a poetic exploration of the migrant experience.

Some Introductory Notes on Yota Krili's Poetry

Professor Vrasidas Karalis

Sir Nicholas Laurantus Professor of Modern Greek

University of Sydney

For me, reading poetry in Greek today in Australia is an act of stubbornness and yet an act of revelation. Actually that's the way I see Yota's poetry; as both an act of persistence and an act of faith; she keeps writing poetry when the whole genre is marginalised and she writes poetry with the innocence and the surrender of a soul who hasn't been expelled from paradise and lives in a perpetual state of grace. Even when she remembers, she essentially re-members, brings the past experience into completion through imaginative reconstruction; indeed Yota's poetry is an act of faith in the capacity of imagination to sublimate reality without at the same time hiding its shadows, its fears, its secrets. This is poetry, by all means. A process of transforming trivialities into verbal acts of grace, and bringing them together into a symbolic completion.

Yota, and I believe the reader of her poems, feel intensely the wonder and the magic which are produced by such transformation. Her poetry sensitively portrays the nuances between things and between states of being. Even when she is political, the humanist vision of her poems transforms the message into something beyond its explicit recipient. Yota’s poems stress the fluidity of existence, the passage of time and foreground the vitality and the optimism of her universal vision; a vision of empathy, compassion and mutuality.

Her language is like an all-receiving mirror ready to accept and incorporate disparate and almost conflicting impressions into a complete image. Her poems talk about what the past with a mild nostalgia for something which remains nameless and beyond comprehension; the poet wants to find meaning to everything she experienced in Greece or in Australia. This is not another case of migrant poetry, or poetry of displacement or of traumatic loss. This poetry does not revert to such unfortunate common places of so many other books which talk about the past. Through the creative force of her language these poems both in English and Greek map the territory of a spiritual journey of self-recognition and self-realisation.

I am deeply impressed by the interdependency of both texts in this edition; whoever is able to read both texts is really puzzled not by the accurate translation of the poems (since some of them were written in initially in English and others in Greek) but by the correlation of these texts, by the co-evolution in both languages of her poetic imagination and inventiveness. Through such symbiosis of languages we can see today in Australia the importance of bilingual not to say multilingual poetry as it is created and arrive at the appropriate conclusions about poetry as the ultimate linguistic activity.

However behind the serene atmosphere of recollection, her poetry expresses feelings of intense unrest and agitated quest for that anonymous presence that creeps and slips through our fingers and yet we are unable to locate it, to see it to nail it down and make it stable, fixed and definite; essentially time. I don't see her poems as nostalgic recollections of Greece or of anti-Vietnam war rallies but as attempts to nail down time by creating icons of luminous clarity and interpersonal connection.

Her poems express the force of flowing impressions of life around us; they do not distinguish between people. They see everything in a continuum of impressions, shapes, colours, signs and gestures without differences or contradictions. These poems talk about the past not because the poet has grown old but because she has outgrown it; she has assimilated past and present into the complete unity of an aesthetic revelation; sufficient in itself and more than that of multi-dimensional character, not bound by the past but liberated from it.

Yota’s poems in both languages reveal the liberating potential of language; unlike structuralists and post-structuralists I insist on looking at poetry as the space of inner freedom where even the constraints of form and genre become catalysts for the enhancement of feeling for the dramatic performance of our own personal reality. Language is the only refuge. By writing language the poet becomes language and creates an ideal identity for her readers. She becomes herself and at the same time gives to her readers an identity by situating them in time in front of her. Yota’s poetry is based on the enhancement of interpersonal engagement, as we look at each other's eyes with expectation and awe.

This is the reason I avoid calling Yota’s poetry migrant poetry; it goes beyond such classifications and let's hope that one day literary criticism in Australia will open up and reach out without collapsing, and discover the quality of tone and the density of voice that enriches Australian tradition as Yota herself describes: (Travelling p.18)

By writing in Greek in Australia she perpetuates not simply a tradition but an identity, not only a heritage but a mentality. By writing in Australian English she expands the expressive potential of the language and adds a new dimension to the Australian sensitivity.

Language is a planet of living, a biosphere; an existential concern in which Yota re-configures through the sensibility of the dispossessed and the hope of the creator.

4 October 2003

Sir Nicholas Laurantus Professor of Modern Greek

University of Sydney

For me, reading poetry in Greek today in Australia is an act of stubbornness and yet an act of revelation. Actually that's the way I see Yota's poetry; as both an act of persistence and an act of faith; she keeps writing poetry when the whole genre is marginalised and she writes poetry with the innocence and the surrender of a soul who hasn't been expelled from paradise and lives in a perpetual state of grace. Even when she remembers, she essentially re-members, brings the past experience into completion through imaginative reconstruction; indeed Yota's poetry is an act of faith in the capacity of imagination to sublimate reality without at the same time hiding its shadows, its fears, its secrets. This is poetry, by all means. A process of transforming trivialities into verbal acts of grace, and bringing them together into a symbolic completion.

Yota, and I believe the reader of her poems, feel intensely the wonder and the magic which are produced by such transformation. Her poetry sensitively portrays the nuances between things and between states of being. Even when she is political, the humanist vision of her poems transforms the message into something beyond its explicit recipient. Yota’s poems stress the fluidity of existence, the passage of time and foreground the vitality and the optimism of her universal vision; a vision of empathy, compassion and mutuality.

Her language is like an all-receiving mirror ready to accept and incorporate disparate and almost conflicting impressions into a complete image. Her poems talk about what the past with a mild nostalgia for something which remains nameless and beyond comprehension; the poet wants to find meaning to everything she experienced in Greece or in Australia. This is not another case of migrant poetry, or poetry of displacement or of traumatic loss. This poetry does not revert to such unfortunate common places of so many other books which talk about the past. Through the creative force of her language these poems both in English and Greek map the territory of a spiritual journey of self-recognition and self-realisation.

I am deeply impressed by the interdependency of both texts in this edition; whoever is able to read both texts is really puzzled not by the accurate translation of the poems (since some of them were written in initially in English and others in Greek) but by the correlation of these texts, by the co-evolution in both languages of her poetic imagination and inventiveness. Through such symbiosis of languages we can see today in Australia the importance of bilingual not to say multilingual poetry as it is created and arrive at the appropriate conclusions about poetry as the ultimate linguistic activity.

However behind the serene atmosphere of recollection, her poetry expresses feelings of intense unrest and agitated quest for that anonymous presence that creeps and slips through our fingers and yet we are unable to locate it, to see it to nail it down and make it stable, fixed and definite; essentially time. I don't see her poems as nostalgic recollections of Greece or of anti-Vietnam war rallies but as attempts to nail down time by creating icons of luminous clarity and interpersonal connection.

Her poems express the force of flowing impressions of life around us; they do not distinguish between people. They see everything in a continuum of impressions, shapes, colours, signs and gestures without differences or contradictions. These poems talk about the past not because the poet has grown old but because she has outgrown it; she has assimilated past and present into the complete unity of an aesthetic revelation; sufficient in itself and more than that of multi-dimensional character, not bound by the past but liberated from it.

Yota’s poems in both languages reveal the liberating potential of language; unlike structuralists and post-structuralists I insist on looking at poetry as the space of inner freedom where even the constraints of form and genre become catalysts for the enhancement of feeling for the dramatic performance of our own personal reality. Language is the only refuge. By writing language the poet becomes language and creates an ideal identity for her readers. She becomes herself and at the same time gives to her readers an identity by situating them in time in front of her. Yota’s poetry is based on the enhancement of interpersonal engagement, as we look at each other's eyes with expectation and awe.

This is the reason I avoid calling Yota’s poetry migrant poetry; it goes beyond such classifications and let's hope that one day literary criticism in Australia will open up and reach out without collapsing, and discover the quality of tone and the density of voice that enriches Australian tradition as Yota herself describes: (Travelling p.18)

By writing in Greek in Australia she perpetuates not simply a tradition but an identity, not only a heritage but a mentality. By writing in Australian English she expands the expressive potential of the language and adds a new dimension to the Australian sensitivity.

Language is a planet of living, a biosphere; an existential concern in which Yota re-configures through the sensibility of the dispossessed and the hope of the creator.

4 October 2003

Excerpts from Triptych's Introduction

Helen Nickas

Latrobe University, Melbourne

Triptych Editor and Publisher

Owl Publishing

The first section titled Patchwork and prefaced with the line, “Glory be to God for dappled things” reflects the multifariousness of the poems. They center on travel, adventure, nature, dreams, memories, politics, philosophy, observations, portraits. The speaker is a member of a world community not just a Greek migrant. As a traveler, and narrator is certainly not a tourist in popular resorts but an explorer / adventurer in troubled regions like Colombia, Cuba, Vietnam, or a backpacker in Australia, …gives us vivid and empathetic portraits of aborigines: empathy by an immigrant for the plight of people who, likewise, live in the periphery… This section also includes many poems which capture ‘moments’ in our lives when the ordinary, everyday happening becomes something memorable, striking a universal chord.

The second section Memories is prefaced with the epigraph “Let us not allow the dead to be killed” which indicates an obligation on the poet’s part to record the past from her own present perspective and to honour and immortalize the inhabitants of her past for posterity. In her portraits of her mother, father, siblings, as well as the family house, the seasons and, generally, the physical environment of rural Greece, she describes, as Helen Kolias has aptly observed, “time-honoured activities associated with the life cycle and the changing of seasons. …The poet’s descriptions of village life are so evocative that only one with such a deep affinity with it could give. They also reflect the poet’s preoccupation with the problems of the world and indicate her concern for the degradation of the natural environment.

The third section Laya tells the story of migration. People like the ‘laya’, the black sheep, found themselves to be outsiders especially after WW II and the Civil War in Greece and were forced to migrate. Inevitably they were to experience alienation and displacement in the new country, where their language was redundant and the way of life different. The poet depicts their bewilderment, their struggles to survive, their failures, their pain. The proverb which prefaces this section “Everyone takes wood from a fallen tree” aptly illustrates the exploitative condition of the migrants.

2003

Latrobe University, Melbourne

Triptych Editor and Publisher

Owl Publishing

The first section titled Patchwork and prefaced with the line, “Glory be to God for dappled things” reflects the multifariousness of the poems. They center on travel, adventure, nature, dreams, memories, politics, philosophy, observations, portraits. The speaker is a member of a world community not just a Greek migrant. As a traveler, and narrator is certainly not a tourist in popular resorts but an explorer / adventurer in troubled regions like Colombia, Cuba, Vietnam, or a backpacker in Australia, …gives us vivid and empathetic portraits of aborigines: empathy by an immigrant for the plight of people who, likewise, live in the periphery… This section also includes many poems which capture ‘moments’ in our lives when the ordinary, everyday happening becomes something memorable, striking a universal chord.

The second section Memories is prefaced with the epigraph “Let us not allow the dead to be killed” which indicates an obligation on the poet’s part to record the past from her own present perspective and to honour and immortalize the inhabitants of her past for posterity. In her portraits of her mother, father, siblings, as well as the family house, the seasons and, generally, the physical environment of rural Greece, she describes, as Helen Kolias has aptly observed, “time-honoured activities associated with the life cycle and the changing of seasons. …The poet’s descriptions of village life are so evocative that only one with such a deep affinity with it could give. They also reflect the poet’s preoccupation with the problems of the world and indicate her concern for the degradation of the natural environment.

The third section Laya tells the story of migration. People like the ‘laya’, the black sheep, found themselves to be outsiders especially after WW II and the Civil War in Greece and were forced to migrate. Inevitably they were to experience alienation and displacement in the new country, where their language was redundant and the way of life different. The poet depicts their bewilderment, their struggles to survive, their failures, their pain. The proverb which prefaces this section “Everyone takes wood from a fallen tree” aptly illustrates the exploitative condition of the migrants.

2003

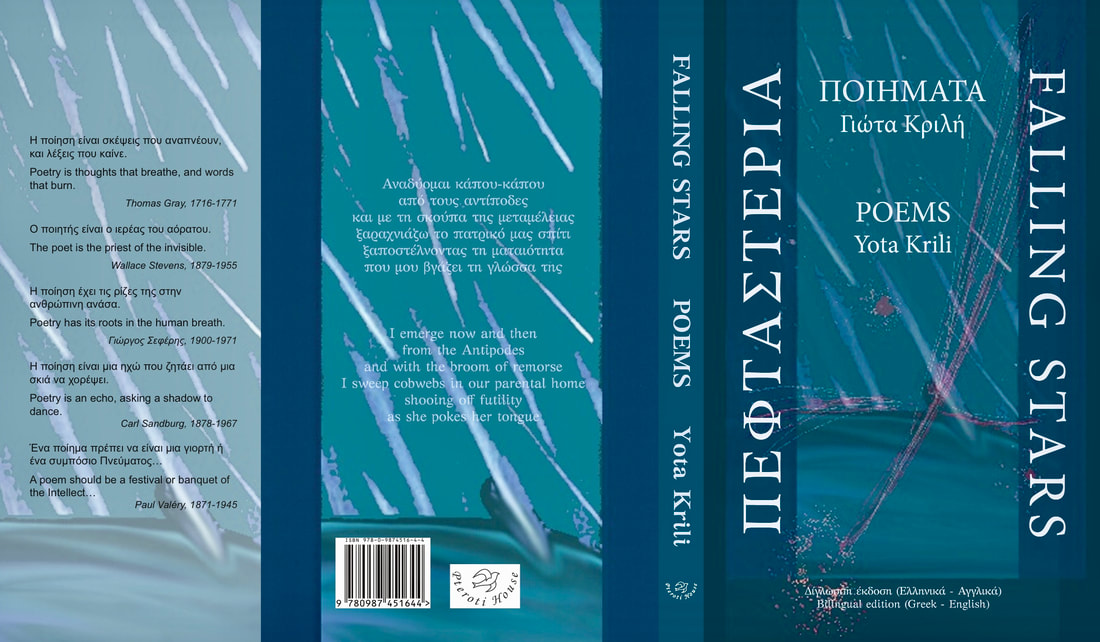

Falling Stars

Yota's award winning poetry anthology "Falling Stars" was written over a period of 50 years and published in 2018.

Many of the poems featured in the anthology were unpublished previously.

Many of the poems featured in the anthology were unpublished previously.